Date Completed: July 2012

Difficulty: Novice

Method of Travel: Canoe

Region/Location: Central Ontario; Algonquin Provincial Park

Trip Duration: Three days

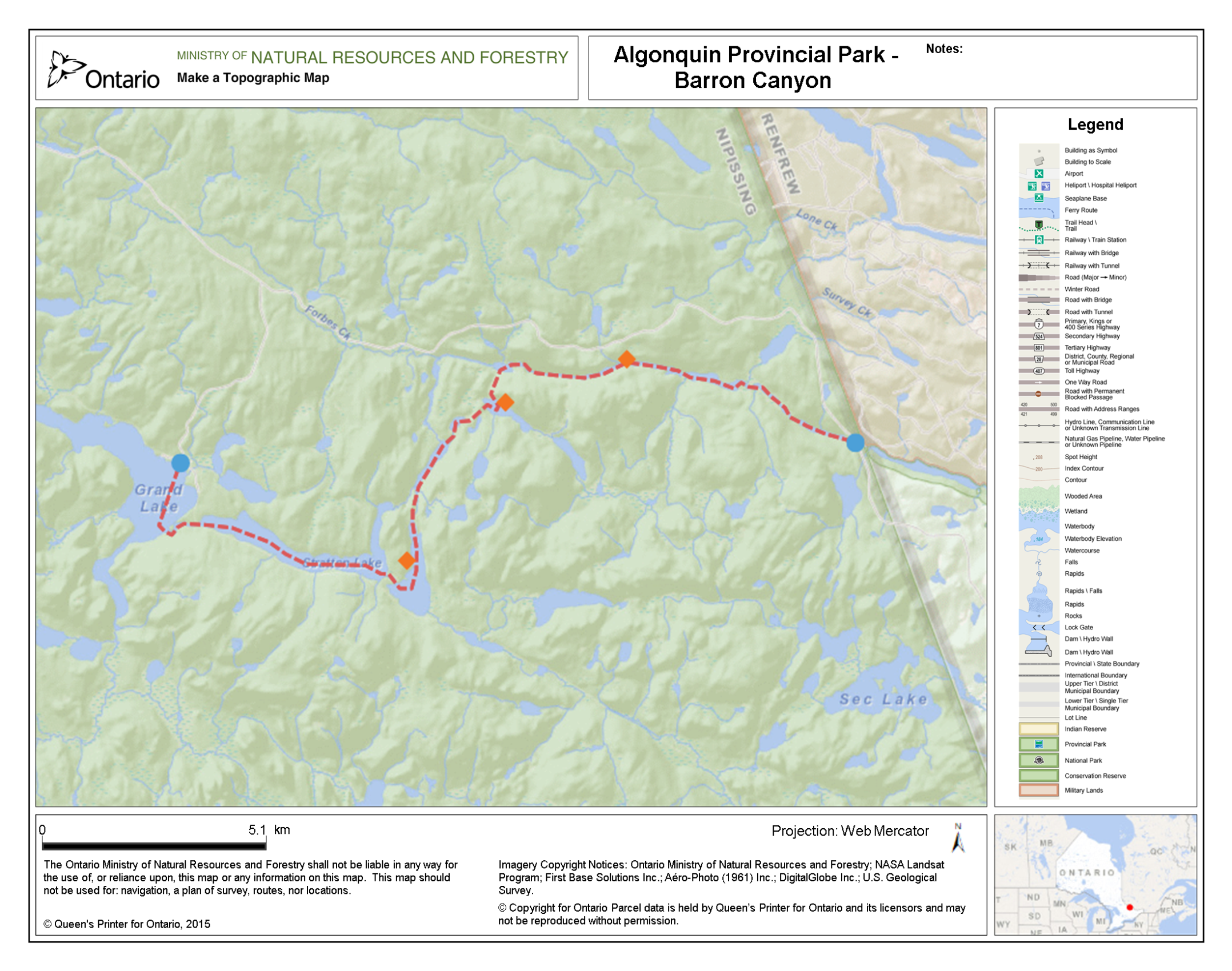

Distance: ~24km total (~21km on lake/river; ~3.2km over 9 portages)

Loop: No

Fees/Logistics: Park permit/parking fees required; shuttle required.

Trip Journal:

From its headwaters at Clemow and Grand Lakes in Algonquin Park, the Barron River flows east, cutting through rugged expanses of Canadian Shield, en route to the Petawawa and Saint Lawrence Rivers. The Barron follows the Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben, a 55km wide geological rift valley, formed some 450 million years ago by shifting of the Earth’s crust. This expansive depression extends today between Lake Nipissing and Montreal.

The Barron Canyon itself, carved by glacial melt-water 10,000 years ago, is the primary highlight of the region. Towering 100 metre granite cliffs rise dramatically out of the river; their walls coated in a peculiar colour of rusty orange, largely due to the presence of Xanthoria lichen that clings to the rocks of the gorge. Along the edge of the river, large mounds of talus, reminiscent of the mountains of the west, have accumulated along the canyon given thousands of years of erosion.

The canyon and the forests that surround it are studded with an assortment of pine, spruce, hemlock and cedar, with deciduous aspen and birch present as well. Deep in the canyon, as a legacy of its cold glacial past, travellers can find rare and regionally unique, arctic and sub-arctic plants, such as the White Mountain Saxifrage.

A rich human history characterizes in the region as well. The Barron, named for John Augustus Barron, a Member of Canada’s Parliament, was an important logging corridor in the 19th century and was a site of annual logging runs. Graves of ill-fated lumberjacks and timber runners can still be found along its shores.

At Grand Lake, near Algonquin’s Achray Campsite, is the place that inspired one of Canada’s most beloved works of art. It was here, on the shores overlooking the beautiful hills of Carcajou Bay that Tom Thomson sketched a solitary jack pinein 1916. The following year, which also happened to be the year of his drowning at Canoe Lake, Thomson completed a seminal piece, The Jack Pine, based on that sketch at Grand Lake. It is thought that Grand Lake and those same hills, also inspired Thomson’s masterpiece, The West Wind. Today these immortal works – which all Canadians should endeavour to witness – hang respectively on the walls of the National Gallery in Ottawa and the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Toronto.

An excerpt from Tom Thomson’s Jackpine, by Henry Beissel:

Bent but never broken by the brute winds

and weathers of this northland the solitary jackpine

towers over lichen-crusted rocks

where a forest fire once gave life to its seed.

Its gnarled hands now reach over the hills

blueing deep into the citreous green twilight

trailing the sun on its retreat over the horizon

from where its fires can still touch the pine’s

slender fingers. The belted kingfisher has gone

who dove from its branches with a rattle

and a splash to catch the slippery fish. Darkness

is rising from its roots and will soon grey the air

to black that’s already trembling with the hoot

of the great horned owl perched out of sight

to ambush some hapless nocturnal. And yet

the light is at peace with the tree and the lake.

Calmly it amplifies the beryline silence brooding

on the waters where Tom’s spirit rests forever

alongside the sky stretched out in the shadow

of the jackpine that holds heaven and earth

together in an embrace encompassing the hills

the lake, the seasons, and the void that fills

the dark spaces between them and infinity.

It was the last weekend of June, 2012, that we chose for our trip through the Barron Canyon. After work on the Friday night, Justin, Lachlan, my dad and I made the four and a half hour drive from Mississauga to Pembroke where we decided to stay the night at one of the local motels, before heading into the park the following morning. Unfortunately, vacancy was low and the price for a few hours of sleep was excessive enough to force us across the street where we decided to put up our tents in a truck stop. We all agreed that camping in a dusty lot between a couple of semi-trailers was a humorous way to start our trip.

I was excited for the trip especially because this would be my first multi-day backcountry canoe trip with my dad.

In the morning, after grabbing a quick bite of food in Pembroke, we drove directly to the Barron Canyon trailhead (on Barron Canyon Road) to catch a glimpse of what our trip would have in store for us. The trail is a brief 1.5km loop that quickly leads to the canyon’s spectacular north rim. We took our time admiring the sparkling river and the mighty canyon walls that envelope it under the morning sun. Dad took a fantastic picture of a hawk cruising between the walls of the canyon below us. Walking this quick trail is an absolute pre-requisite for anyone planning to paddle the canyon for the first time.

Before leaving, we signed our names in the guestbook with the charred end of a twig and drove off to Algonquin Bound Outfitters.

Being that the Barron Canyon route is not a loop, it is necessary to arrange a vehicle shuttle between the take out point before the bridge near Squirrel Rapids and the put in at Grand Lake. The outfitter took care of this for a fee.

At Achray we launched our boats off the beach set out toward the southeast corner of the lake. We were faced with a relatively rocky start to the trip as a stout southwest wind kicked up the waves and we battled to keep the boat straight. In higher winds, crossing the Grand could be a fairly precarious task. After some strong paddling, however, we turned the boat and allowed the winds to push us into the protected bay that funnels into a creek linking Grand Lake to Stratton Lake. To access Stratton, its first necessary to carry over a brief 30m portage at the start of the creek and a dip under an old abandoned Canadian National Railway bridge.

With the wind now at our back, we glided swiftly for about 4km on cresting waves to Stratton’s far end, where we circumvented the designated 45m portage by pulling our boats down a bouldery creek to St. Andrew’s Lake.

St Andrew’s is spacious, hooked-shaped and scenic, shrouded by red and white pines and elegant hills on all shores. On the lake’s far east end, a horizontal scar in the tree line signifies the path of the abandoned rail-line we had crossed earlier in the day.

We camped on one of St. Andrew’s several western campsites in a large, flat grove of red pine and felt fortunate to learn that we had the entire lake to ourselves. For the remainder of the day we lingered around camp, cooked food, and were visited by chipmunks as well as an exceptionally friendly red squirrel that repeatedly climbed over our gear in search of something to eat. Late in the day, Lachlan and I paddled out to the west shoreline to explore an interesting granite outcrop.

The following morning we continued to the end of St. Andrews and over the 500m portage to Highfalls Lake. Highfalls Lake is named for the incredible collection of waterfalls and pools that are clustered around the lake’s southwest end. The area – which is more commonly accessed by Stratton Lake, the Eastern Pines Trail via Achray or the High Falls Trail via Barron Canyon Road – is an extremely popular spot in the summertime. Park visitors can be found here in high volumes lounging on the shoreline, soaking in the pools, and enjoying the “waterslide” – a flat, slippery slab of granite that would not be out of place in a water park.

Accessing High Falls from High Falls Lake, as we did, involves some slight bushwhacking, but is generally not difficult. After tying our boats to a tree limb, we hopped out onto the rugged and rocky shore and followed it until we reached the lower falls. From here, we climbed up and spent a good hour or two swimming and relaxing in the sun before scrambling back to our canoes and travelling northward to Ooze Lake and ultimately Opalescent, over respective 300m and 650m portages.

On Opalescent Lake we found a great spot on the north shore and set up camp. As we pitched our tents, a black ratsnake – Ontario’s largest snake species, measuring up to two metres – slid its way across a nearby log.

The afternoon wore on, and Justin seasoned and cooked a whole chicken over the fire, which we enjoyed with some kebobs, roasted vegetables, whiskey and Southern Comfort – a favourite of my dad’s.

As dusk settled in, I paddled out onto the lake in a canoe in time to be met with a light drizzle. The scene held a gloomy, wild beauty – darkened shorelines with tangled dark grey and purplish clouds above, and to the west the final warm, yellow rays of the ever shrinking sun struggling to pierce through their encroaching canopy; the trickle of rain drops cooling the skin and casting a hypnotic pattern on the monotone water; the call of a loon from somewhere off in the distance. Before long night will fall and the bellow of the timber wolf will echo over the lake in its stead.

The skies were clear again in the morning, and we took advantage of the day with an early start. Opalescent Lake connects to Brigham Lake and the Barron River over a ~700m portage littered with exposed roots and cobblestone.

On Brigham we could sense we were getting close to the canyon. With a quick portage around Brigham Chute, and a short paddle down the narrow, bending river, the canyon’s walls slowly began to reveal themselves. A hush came over our group as we cruised forth, admiring the magnificent walls that now cradled our two canoes. We spent an hour or so slowly paddling and resting under the canyon’s sheer cliffs, marvelling at their height above us.

At the end of the canyon is an excellent campsite on a small outcrop. Since the beginning of the trip we had been hoping to camp at this location as we knew it would provide a scenic vista and easy access back into the canyon to the west. On approach of the site, however, we noticed a group of three canoeists standing ashore. As we got closer, they surprisingly entered their boat and offered the site to us, explaining that they believed that they had booked a site further down river. I’m sure they regretted abandoning the site, as within 10 minutes of their departure a hard driving rain commenced. We scrambled for our rain jackets and shelter.

After the rain subsided, Lachlan and I tried our hands at fishing off shore, to marginal luck, while a massive raven – clearly habituated to the site – patrolled the skies over head.

The clouds had surrendered to clearer skies and, before long, the purple vapours of evening set in. As night crept closer, we paddled back into the canyon to enjoy its quiet splendour once more. The sheer cliff faces were now transformed to monolithic masses of darkness against the orange sky. The air was clear, but a chill lingered and we wondered facetiously whether we were at all in the same place we had paddled through only a few hours before. A warm fire and bed waited for us back at camp.

The following morning we woke late and cooked a hearty meal of eggs and bacon. This was our last day on the water and we were in no hurry to return home.

As we slowly packed up our gear, the raven had returned and, to our amazement and gaiety, covertly stolen Lachlan’s apple off a log. With the raven well-fed, we disembarked in good spirits on the final five kilometre trip back to our cars.

Note: photographs by Ebbe Thomsen and Erik Thomsen.