BY ERIK THOMSEN

The cold subarctic gales, driving rains, unrelenting headwinds, the ruggedness of the lands, the turbulence of the waters – the Missinaibi and Moose Rivers in northern Ontario may well put you on a threshing floor and strip you down to your rawest emotions. Isolation, desolation, fear, and at times, utter despondency; nature here is unforgiving, uncompromising, and is capable of testing the upper limits of your endurance and fortitude. You may question why you do it.

But it is here that you will find colours you have never seen and Gods that you never knew existed. Swallows will flicker as they feed in the dimming dusk, the Aurora Borealis will dance through the northern sky as it has for aeons and you will edge closer to answering the great questions.

On these mighty rivers, yet free and untamed, you will find a glory that binds all, through the ages, who have ever gazed over the expanses of the wild and endeavoured to solve the mystery beyond.

It was under a purple pre-dawn sky, on an unseasonably crisp July morning that I sat on the grassy banks of the Missinaibi in Mattice, Ontario, consumed by that very sense of mystery. Amongst the early morning bird song and through a swirling mist, I watched the river abidingly as the ascending sun crept slowly above the horizon. In a few hours, our group of four longtime friends would finally launch our canoes and begin our 316km journey to the isolated Cree community of Moosonee, on the edge of James Bay.

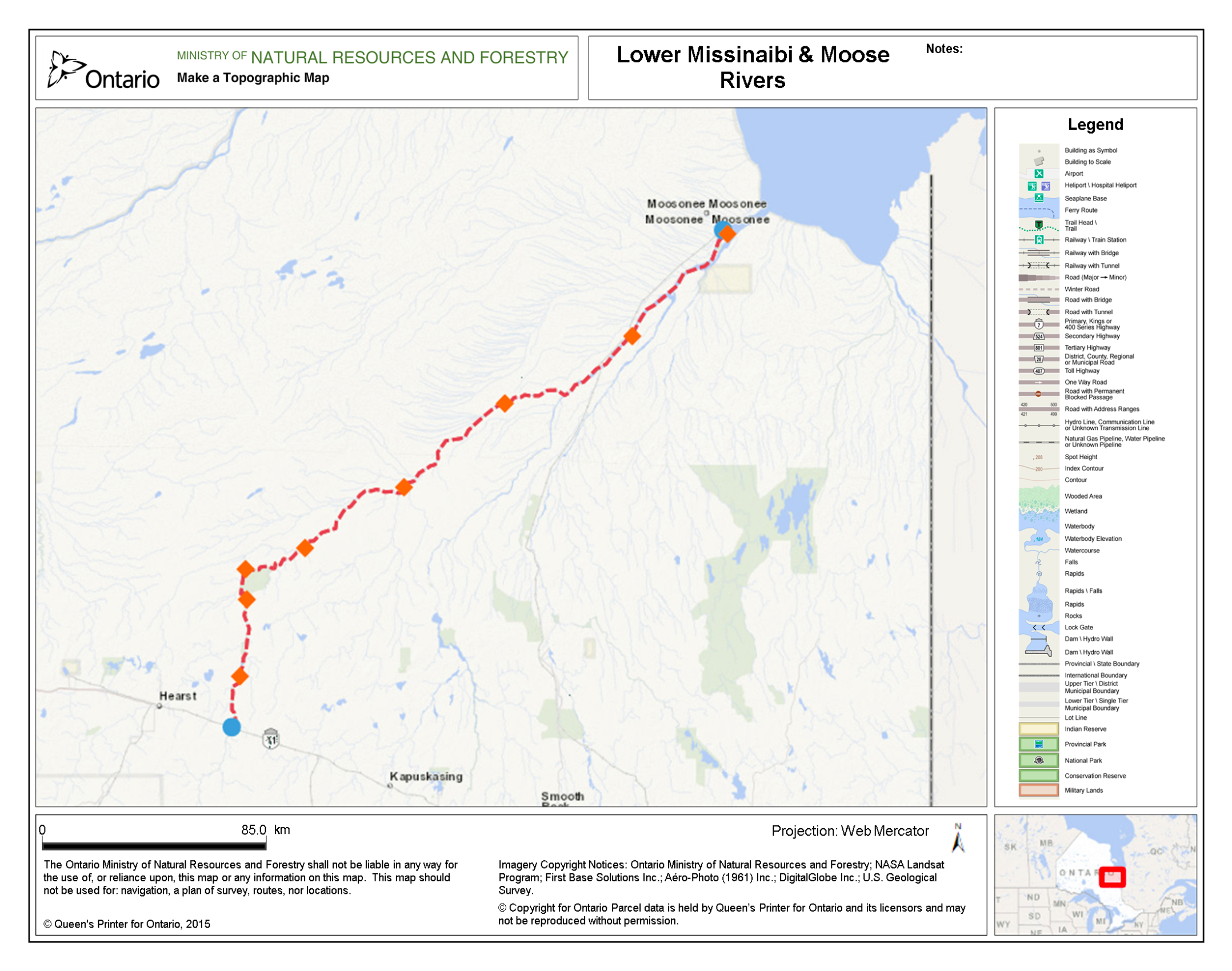

For many years I had traced the course of the Missinaibi and Moose Rivers on my topographic maps. I had pondered the sweeping breadth of the mixed boreal forest that surround the glacier scoured shores of Missinaibi Lake, in the heart of the Chapleau Game Preserve. From there, the headwaters of the Missinaibi, I followed its narrow serpentine flow northward, past the train bridge and abandoned Hudson’s Bay Company post at Peterbell, over the notorious, raging waters of Greenhill Rapids, and beyond the town of Mattice. I envisioned this rolling river and its rapids cutting deep through thick stands of black spruce, balsam fir and tamarack.

Continuing north and northeast, I contemplated the immense, earthshaking power of Thunderhouse Falls – the place where the river begins its dramatic, roaring descent off the Canadian Shield and into the Hudson Bay Lowlands. I thought of Algonkian shamans that practiced rituals here over millennia, the traders and Bay men that used the area as a meeting place to exchange their goods, and the many doomed canoeists that had been caught in the alluring flow of the river above the falls before being drawn into its deadly maw.

Beyond Thunderhouse, I studied the Missinaibi’s sudden confluence with the Mattagami to form the Moose River, and I wondered about the expansiveness of the sky – this is a region known for its vast, low-lying, impenetrable muskeg and stunted vegetation. In the lowlands, it is the mercurial multi-tonal sky that prevails as the dominant feature of the landscape.

At last, I traced the ever-widening river further north to Moosonee and Moose Factory, further still to James Bay and ultimately to the Arctic Ocean itself.

As I looked over those maps, I thought of the bald eagle soaring high above the spires of its lonely domain; the timber wolf roaming wild and free through the dank hollows of the dark northern coniferous taiga and this place of shadows; the woodland caribou, unconstrained as the river itself. I thought of the power of the moon and how it heaved the cold ocean waters of the Bay 15km in-land and up-river. I thought of the smoky-white beluga breaching the briny waters near the mouth of the Moose, and the mighty polar bear rambling along the desolate, cobble coastline in the southern most extent of its global range. This is how our rivers were meant to be.

Over its magnificent, free flowing course, the Missinaibi takes its travelers back 8,000 years to the retreat of the 3 km thick Wisconsin Ice Sheet, which covered all of Ontario during the last ice age. With the melting of the glacier, the uplands of the Missinaibi region became habitable to hunters of the central plains, and over millennia, the migration of these hunters followed the retreating glacier further north.

At the time of European arrival and settlement in the 16th century, the river was well utilized for hunting and travel by Michipicoton Ojibwe in the south and Moose Cree in the north. By the late 1770s, and for 140 years thereafter, the Missinaibi and Moose Rivers became one of the most important canoe routes in the North American fur trade as the most direct link between the posts on Hudson Bay and Lake Superior.

But unlike many other famous, historical routes – the Ottawa, the Mattawa, the French – signs of modernity here remain sparse. Bridges span the river only four times in its course, and beyond the town of Mattice, the river is virtually devoid of development and exploitation. Incredibly, pictographs, ruined Hudson’s Bay Company forts, and gravesites survive to this day. These age-old relics serve to remind the traveler, unequivocally, that every moment of his journey in this precious land is fleeting.

It was with these thoughts that our journey down the Missinaibi finally commenced on that chilly morning in July. Gazing down this vast, sweeping artery is a clear, ancient pathway, shrouded symmetrically by stately emerald palisades atop sloping grassy shores. The landscape is simple, if not austere. The dark river winds far into the distance, over turbulent rapids, falls and boulder fields.

It took our group two days, paddling almost 60 km from Mattice, into stiff southerly headwinds, to reach Thunderhouse Falls. Arriving there in the dim iridescent glow of the late afternoon, we were greeted by a large golden eagle perched, like a sentry, atop the twisted skeleton of a dead tree. Under the ominous flight of this majestic creature, we continued down the 1,650 m portage trail towards the cliffs of Thunderhouse canyon.

Thunderhouse is comprised of three volumous, cascading drops that collectively measure upwards of 15 m. The dark, yellowish waters of the Missinaibi, in high water, crash over those drops with a violence that would perhaps rival any wild river in the province. Below the falls, the river settles placidly into a glorious canyon set 35 m below the forest. The canyon is punctuated by a lone pillar of gneiss, known as Conjuring House Rock, which towers 20 m out of the water.

We set camp on the brink of these cliffs and gazed contentedly over the serenity of the lower falls, Conjuror’s Rock and the canyon’s east wall for a long time. We admired the reflection of the dying sun as it glimmered off the foamy waters below and gave audience to the canyon even as darkness took hold and the northern winds began to swirl.

The wind came quickly and with scant warning. Dark clouds swept across the purple twilight; foliage began to roar, trees began to sway and crackle; our fire raged in a wild, uncontrollable frenzy; heavy drops of rain battered our tents as thunder crashed above. The canyon, in a glorious, untamed fury, had come alive.

The next day, through scattered rains, we continued our descent off the Shield and encountered our next major obstacle – Hell’s Gate Canyon. The massive cascading falls that characterize this secondary canyon are dangerous and caution must be exercised on approach of the portage, given the speed of the river and obscured trailhead. Once ashore, we struggled through the knee-deep mud that glazed much of 2,300 m trail. Unfortunately, both the deteriorating conditions and thick, twisted brush shrouding the trail discouraged us from exploring the canyon to any great extent. Thus, forward we travelled onto the river and to the high clay bluffs of Bell’s Bay, where we laid our shelter for the night.

While we dreamed of warmer days ahead, the following day brought no reprieve. For most of the morning we waited for steady rains to subside, but failing that, decided to launch our boats under a lull. Within 2 km the rainstorm intensified, and with no obvious place to gain shelter on the scrubby, waterlogged banks, we forged ahead. After 10 more km – our rain gear saturated, and a hypothermic chill affecting us all – we finally staked shelter at mouth of the Coal River. Here, with a depleted morale, we waited for the rain to abate again, before getting back into our boats and pushing to camp at Piwabiskau River.

For 120 km and three days of travel past Thunderhouse Falls – and despite it being early summer – we endured cold temperatures, soaking rains, desolate skies and steady headwinds. Our battered muscles struggled for every centimetre of progress. Those days invoked harsh lessons on the dispassionate and fickle indifference of Nature and the futility and meagreness of humanity within it.

It wasn’t until our last afternoon on the Missinaibi, before its confluence with the Mattagami, that the conditions began to improve. That afternoon, the sun gleamed through the clouds and warmed our skin for the first time in almost a week. The next day, though the headwinds remained persistent, we finally paddled onto the Moose River with large swaths of blue-sky overhead.

Almost immediately after reaching the Moose the landscape changed dramatically again. The river widened significantly – almost a kilometre in places – and was speckled with wild islands and gravel bars. The trees and vegetation, sitting atop the distant banks of the river grew short, clearly influenced by the long, harsh subarctic winters of the region. At times it was possible to be 400 m from shore and resting in just 20 cm of water. In other instances, the river became deep and susceptible to large waves.

The day grew late – it was our eighth evening on the river and the sun was suspended in the sky. At around 9 o’clock we pulled our boats onto a large bar of sand and cobblestone in the middle of the river. The island held no trees, but was crowned with shrubs and offered sufficient respite.

We climbed from our canoes, pulled them onto the land and began to stake out our shelters. I erected my tent in a protected groove near the middle of the island. This location afforded a supreme southerly vista across this expansive low-lying portion of the Moose. The river here stretched for a kilometre from bank-to-bank and distant shores were visible for many kilometres to both the north and the south.

Upon building my shelter, I escaped into the brisk northern air to explore the island and collect driftwood for a fire. The sun, at this point, was setting slowly in the most incredible array of orange and pink that, perhaps, I’ve ever seen. Bank swallows emerged from little holes in the sun-baked riverbank on the western side of our shrubby island. Hundreds of them came from their nests and enveloped the air around me to feed on the insects in the cooling summer air.

Before long, the setting sun finally dipped below the horizon, and the one-by-one the stars of the universe slowly revealed themselves overhead. We built our mangled driftwood fire high, on that sandy, rocky shore, to ward off the chill of night. In that moment, I stood there thinking about the glory that surrounded us in contrast to the toil we had left behind. Above, the northern lights emerged and began their ancient dance.

After a decade of wilderness adventure, it was here, above this rocky shoal in the land of the endless tangerine sky, that I learned about redemption. Things will be taken from you – and the wilderness is the most implacable taker of things – but I know this: find the strength to endure and every sense will be heightened; persevere and every second will move too fast; overcome and the world will be full of uncommon beauty. Go outside and enjoy this bounty we have been blessed with, for the rivers, here, are still wild.

I think about that day often, and wonder how many others have passed that might compare to it – the sun and clouds in the right place, the water, the breeze, the moon suspended in the dusk. But even with all those ingredients it would be impossible to replicate that feeling of completeness that I experienced that evening, without the moments of hardship that came prior.

Our journey to Moosonee and back to civilization concluded the next day. The final 60 km leg of the trip took us past the confluence of the Abitibi River and boiling Kwetabohigan Rapids. The riverbanks continued to stretch further from us on each side and the tidal effects of the river, with their elongated swells, became impossible to ignore. On this last day, we paddled again into headwinds, but this time under clear blue skies, and by the time the sun fell, the warming lights of Moosonee appeared in the distance. As we paddled toward our final destination, we skirted the shore of Bushy Island and Tidewater Provincial Park, and there, atop the skeleton of a large dead tree, in the yellow light of evening, a golden eagle sat and watched us, as we paddled into the sky.