Date Completed: August 2020

Difficulty: Advanced due to wind/waves on large lakes, technical rapids and isolation

Method of Travel: Canoe

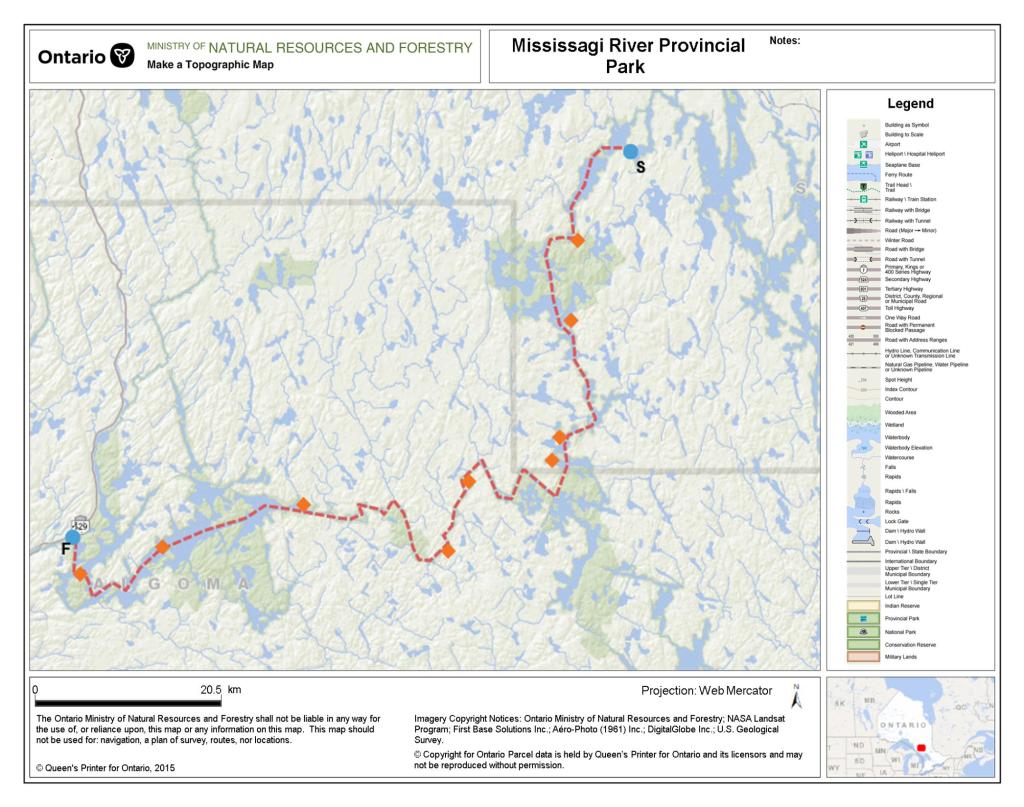

Region/Location: Northeastern Ontario Ontario; Mississagi River Provincial Park

Trip Duration: 11 days

Distance: ~143km total (~79km on lake/river; ~5.6km over 23 portages)

Loop: No

Fees/Logistics: Non operating park (no permit or parking fees); shuttle required

Trip Journal:

Prologue

In the early Spring of 2019, while on a hiking trip through Frontenac Provincial Park, I sat by my campfire under the leafless silhouette of a stand of tall oak trees as a cloudy evening crept in. Earlier the day before, I had parted company with my two hiking companions, who had matters to attend to back home. I, alternatively, opted to stay in the park and hike through the woods for a few more days. Thus, I found myself alone in the forest, amongst the dark green mossy boulders, blankets of brown leaf litter from the prior fall, the ever-darkening trees and my fire.

After finishing a hearty stew, I gathered my flask of whiskey, lay down alongside the roaring fire and opened up “Book Two: Mississauga”, the second part of Grey Owl’s seminal 1936 work, Tales of an Empty.

While I have explored his work on many occasions since that time, I found something spellbinding in reading this tale of the great Mississagi River under the gloom of that early spring night. Perhaps, it was the lonesome forest around me that pushed me through a portal in the pages and teleported me back to the golden age of that wild place, perhaps it was the eloquence of his prose or perhaps it was simply the whiskey. Regardless, I found myself entranced, and I longed for an adventure on the river of a hundred ghosts.

“River of a hundred ghosts….sublime in your arrogance, strong with the might of the Wilderness, even yet must you be haunted by wraiths that bend and sway to the rhythm of the paddles, and strain under phantom loads, who still tread their soundless ways through the shadowy naves of the pine forests, and in swift ghost-canoes sweep down the swirling white water in a mad chasse galerie with whoops and yells that are heard by no human ear. Almost can I glimpse these flitting shades, and on the portages can almost hear, faintly, the lisping rustle of forgotten footsteps, coming back to me like whispers from a dream that is no longer remembered, but cannot die.” (Grey Owl, 1936)

Prior to that evening, I was no stranger to the Mississagi – I had read reports of voyages down the river and heard tales of its allure from other canoe men. I knew of its storied history – the exploits of Grey Owl, the timber runs, the canoe brigades. But from that evening, the river, in my mind at least, became something that ceased inanimacy and gained a living character.

Today, having now run the Mississagi – in traversing her rapids, witnessing her fickle moods, in taking her fish and bathing in her waters, in wondering at her distant horizons, and in beholding meteors from the heavens crashing silently to earth over her dark shores – I can say that this is a river that indeed lives. It is true that scant physical evidence of those old days have withstood the unforgiving seasons. It is clear that humankind has attempted to silence and tame this waterway through the industrial pursuits of energy extraction and logging. But make no mistake – this is a river that, for the better part of its course, yet remains wild and free.

In the summer of 1912, Tom Thomson – one of our country’s most beloved artists – ran the Mississagi from Biscotasing or “Bisco” to Lake Huron over two months. In a subsequent letter to a friend, Thomson remarked that the Mississagi was “the finest canoe trip in the world.” While we can only guess what precisely impelled Thomson to scribe those words, it is clear that the Mississagi still undoubtedly retains the magic that he must have felt as he sat on its rocky shores and sketched the wild panoramas that surrounded him that summer.

As you embark, perhaps, on your own journey down the Mississagi, please remember that in exploring these immense and formidable landscapes, we not only draw ourselves closer to the earth, our home, but we also rekindle the glory of our country’s formative years when the land was younger, before the ceaseless march of the modern world. When we carve through the emerald cathedrals of the Mississagi, we reawaken the ghosts of a still wild kingdom, so that they may sing and chant and paddle once more.

History of the Mississagi Basin

The land that contains the Mississagi, east of Lake Superior and north of Lake Huron is ideal for canoe tripping. The old precipitous formations of volcanic rock that characterize this part of the Shield country have been carved and molded by ice sheets, winds and extreme weather over aeons and in dramatic fashion. Massive cliffs and crags are common throughout the region, while mixed forests of pine, spruce, maple, birch, aspen and others envelope a collection of thousands of rivers, wetlands and island-speckled lakes.

The extent of historic Indigenous presence along the Mississagi is not well known. However, there is evidence to suggest that the river and lakes of the Mississagi were travelled and used by Aboriginal populations for hunting and habitation. Notably, Indigenous encampments and other sites of importance are known to have existed at the mouth of the river and on Upper Green Lake, Rouelle Lake and Rocky Island Lake.

The expansion of the fur trade brought voyageurs and European explorers to the region and outposts were established as early as the late 1700s. The river itself offered an excellent opportunity for trappers and traders to access the bountiful pelt-yielding lands of the interior. North West Company forts soon sprung up at the mouth of the river and on the north shore of Upper Green Lake – these were subsumed by the Hudson Bay Company in the 1820s. Another outpost was established at Biscotasing with the expansion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s, and served as an important centre of commerce in the area.

By the late 1800s, logging operations began to expand to the Mississagi basin with the exhaustion of more southerly forests. An immense network of logging trails, camps, dams and chutes (including a 350-metre flume at Aubrey Falls) were established to support operations that fed enormous quantities of timber downstream and en route to mills on the northern shores of Lake Huron. Timber extraction continues to varying degrees in the Mississagi region to this day, though well beyond sight of the canoe route.

It is worth mentioning here, that one of the most destructive forest fires in Canadian history tore through in the Mississagi River Valley. In May 1948, separate fires in the Chapleau-Mississagi region merged together and scorched almost 750,000 acres of forest before being extinguished three months later. With the fire, large old growth forests and local animal populations were devastated, logging and industrial operations were shuttered and the sky was shrouded in a haze that blocked the sun as far south as Washington D.C. While the valley has rebounded, there is still evidence of this monstrous fire along many portions of the river as seen in the formation of second growth forests of birch and poplar.

Adding to the vibrant history of Mississagi River is the former presence of Archie Belaney – or Grey Owl – in the area. In the early 1900s, Belaney, who was born in England, took up work as a trapper and forest ranger, living in both Temagami and Biscotasing for some time. While in Bisco, Belaney comprehensively travelled and trapped throughout the Mississagi wilderness. Over time, Belaney’s fascination with the Anishinaabe people and culture grew and he adopted and embraced an Ojibwa persona. Under the moniker, “Grey Owl”, Belaney produced a number of writings on matters of conservation and the Canadian wilderness, gained international recognition and conducted speaking tours in several countries, dressed in Ojibwe regalia – even taking audience with the British royal family. Belaney’s true identity was not revealed to the public until after his death in 1938.

Trip Journal – 11 days on the Mississagi

While I had resolved to paddle the Mississagi back at that campsite at Frontenac, it was not until August 2020 that I had the chance to make the trip happen.

This summer a few friends and I had the intention of finally making our pilgrimage to the Northwest Territories to paddle the famous South Nahanni River. Weeks before the trip, however, we were forced to postpone our flights and bookings due to latent travel restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, we found ourselves with a significant amount of free time in early August with no firm plans.

In considering route options, we decided that the Mississagi, with its rich history, scenic topography, varied ecosystems and solitude, would serve as a fantastic alternative.

One of the key decisions that needed to be made was where to access and egress the river. We understood that the river south of Aubrey Falls to Lake Huron, while runnable, would not be ideal for our purposes due to its close proximity to Highway 129 and the fact that this portion of the waterway is interrupted by a series of hydro-electric dams. Conversely, we recognized that the upper expanse of the river, from Biscotasing to Aubrey Falls, would provide a far more remote and pristine experience.

Typically, canoeists begin their journey on the upper Mississagi at one of two places: Biscotasing or Spanish Chutes (not far from the remote community of Ramsay, Ontario). Both options are well inside the Spanish River watershed and involve some upstream (and up lake) travel before crossing into the Mississagi basin and paddling downstream to Aubrey Falls.

Ultimately, we determined that the Spanish Chutes put-in was ideal for our group as it would save us from two days of travel on large lakes from Bisco. This, we agreed, was extra time that could be set aside in case of inclement weather.

Many canoeists attempt to complete the 143-kilometre paddle from Spanish Chutes to Aubrey Falls in seven days (the route from Bisco is 191 kilometres and requires at least nine days). Seven days from Spanish Chutes, however, would have afforded us limited latitude to savour and explore this beautiful wilderness. In effect, our group budgeted 10-days on the water, including two for rain and rest.

After determining our desired route, I began contacting outfitters in the area to assist with a vehicle shuttle. Mike Allen, owner of a cottage rental business named Kegos Camp, north of Thessalon, Ontario, agreed to take our group of six to the put-in point with our three canoes and gear.

My friend Lachlan and I planned to use our jointly owned TuffStuff Novacraft Prospector on the trip. The other four members of our party – Devin, John, Jono and Kevin – needed to rent canoes. Mike explained that Kegos did not provide rental services and as a result, Jono arranged for rentals (in Royalex) through Laurentian University’s Outdoor Centre.

Our plan was to pick up the two rental boats in Sudbury, drive our three vehicles to Kegos Camp, stay overnight on some crown land leased by Mike, then shuttle to Spanish Chutes in the morning. Mike and his two drivers would then return our vehicles to the dam access road north of Aubrey Falls, where we would find them at the end of the trip.

It should be noted, as well, that this is a canoe route that is seldom travelled, especially compared to parks further south. On our first day of travel, we encountered a Ministry of Natural Resources visitor’s log on the Height of Land portage between Bardney Lake and Sulphur Lake. The log suggested that we were only the fourth party to pass through the river that year. It is my belief that the limited traffic within the park is the result of a several factors, including its remoteness, the duration of time required for the trip, the necessity of a lengthy shuttle, and the fact that the access point requires navigating a series of complex, though well-conditioned, dirt logging roads.

Day One – 17.35 Kilometres

Our party departed Toronto in the mid-morning, picked up the two rental canoes in Sudbury and made it to Kegos Camp just before 8:00 p.m. Mike and his wife were very welcoming and indicated that we’d be staying across the road from the main lodge in a crown land meadow that had been formed during the creation of Highway 129 many decades prior. The meadow was flat, grassy and spacious, and overlooked a picturesque bog lined with a collection of tawny daylilies, fireweed, and St. John’s wort.

Dusk settled in as we finished setting up our tents and Mike rolled by on his ATV with some fire wood and clean water for our overnight stay. We chatted about a range of topics and confirmed final plans for the morning, including an 8:00 a.m. departure time. Mike also suggested travelling four kilometres along the logging road past Spanish Chutes and launching our boats at a bay on the southeast arm of Spanish Lake. Acknowledging that this alternative put-in would save us from trudging over an immediate 500-metre portage, we agreed with his suggestion.

Before turning in for the night, we decided to cross the highway and walk the grounds of Kegos Camp. There we found about 10 cozy cottages and some beautiful vantages of Chub Lake at dusk. The camp appeared to be a well-loved and well-maintained getaway location that would be perfect for families and couples seeking some quiet time away from home.

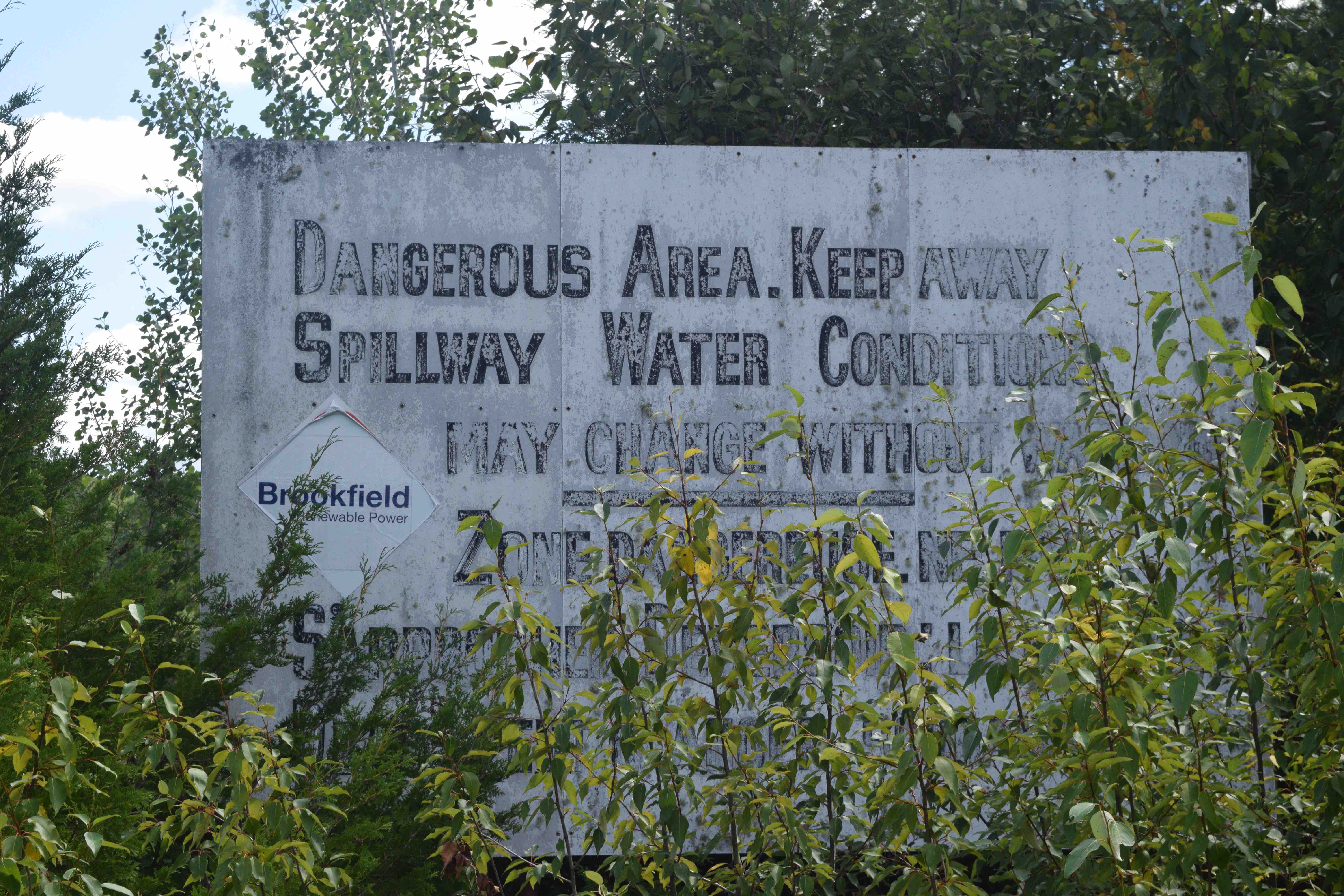

Morning soon came and before long we were heading north on a very scenic (and moose laden) stretch of Highway 129 to Aubrey Falls to drop off Mike’s escort vehicle. For those using Aubrey Falls as a take-out location, it’s important to note that accessing the main lot from the head of the dam would involve a lengthy portage. The best take-out location is the spillway found just north of the main lot off Highway 129, via a gravel service road. While this road leads directly to the gate of the spillway, six or seven parking spots can be found cut into the forest a couple of hundred metres before the water. We surveyed the area, Mike pointed out a good takeout location near the top of the dam, and we continued north again having left one car behind.

After approximately 70 kilometres, just past Five Mile Lake Provincial Park, we swung eastward onto Highway 667, toward Sultan and Ramsay – two tiny communities comprised of a small handful of residences.

During our drive, Kevin and I had engaged in an interesting dialogue with Mike and one of the other shuttle drivers, Tom, on Canadian battles of World War II. In light of this, as we approached Sultan, Mike suddenly suggested that we stop the car at the side of the road. The other two vehicles in our convoy followed suit and Mike led us off into the bush where we came upon a small cemetery.

On the right side of the old cemetery was a flat, grey, traditional military headstone adorned with Canada’s maple leaf emblem and cross. The stone read:

B. 163291 PRIVATE

MANSELL L. SLIEVERT

NO. A. 10 C.A. (INF.) T.C.

9th MAY 1945,

IN LOVING MEMORY

KNOWN TO MANY, LOVED BY ALL

FATHER, MOTHER AND FAMILY

It was somewhat peculiar and unexpected to see this gravestone here, in this isolated locale, as the vast majority of on-duty World War II soldiers were buried overseas. Mike soon explained that this young man, who died at the age of 19 and evidently had roots in Sultan, had actually perished in a motor vehicle collision while on active duty in Vernon, British Columbia.

Before continuing on to Spanish Lake to begin our trip, we wandered the rest of the small graveyard. A number of the headstones were terribly weathered or illegible. We then found one that marked the final resting place of a man named, John Ceredigion Jones, deceased in 1947. A poet and a vagabond, it is the words of Ceredigion Jones, that were immortalized in stone above the entrance to the Memorial Chamber of the Peace Tower in Ottawa to commemorate our fallen heroes. His words read, “All’s well for over there amongst his peers A Happy Warrior sleeps.”

This moment brought me back to my own visit to the Memorial Chamber, a number of years before, and reminded me of a moving verse inscribed on the wall of that sacred room, written by Richard Miles. I thought of the verse and perhaps never felt so grateful to be venturing off into our beautiful wilderness once more:

I go that we may breast

Again the Dorest Downs in zest,

And walk the Kentish lanes where I

Began a larger life knowing

You. Yet if from seething sky

I win reprieve but by the slowing

Crutch or whitened cane, my doom

Will yet have helped to hold in bloom

Old English orchards, and Canadian

Woods unscarred by steel, Acadian

And Columbian roofs unswept

By flame. My mother will be kept

From stumbling down a prairie road

Illumed by burning barns and snowed

By patterned death.

From Sultan we drove south into a web of well-maintained logging roads and soon encountered the small logging and rail community of Ramsay, deep in the bush. Our third shuttle driver, who was travelling in one of the other vehicles, happened to be an author named Darin Fahrer, who had grown up in this area and written about it in his book, “Ramsay – Life in a Northern Ontario Community.”

Not far from Ramsay, we finally crossed over Spanish Chutes and found the entrance to the eastern shore of Spanish Lake. We bid our drivers farewell, and portaged our gear down a 100-metre trail to the lake. The day’s drive began at Kegos Camp at around 8:30 a.m. and it was now half-past noon with the sun beaming overhead.

Spanish Lake is an X-shaped body of water, containing a few sizeable islands and surrounded by boreal forest. We paddled north out of the southeast branch of the lake, turned west and made our way toward a clean 150-metre portage to Bardney Lake. The portage ended at a spacious rock outcrop, abutting a small dam, which we stopped at for a quick swim and lunch. To our surprise, there was an old, red-coloured sunken motorboat offshore from the edge of the trail.

Around the corner, we entered the expansive domain of Bardney Lake and a seven-kilometre paddle on open water confronted us. Though we had a slight headwind for the entire paddle we held no quarrels or complaints – it was simply liberating to be in the open air and on the water again.

At the end of Bardney, we climbed the deceptively long 430-metre Height of Land portage separating the Spanish watershed from the Mississagi watershed. The portage rose steadily before dipping and abruptly ending at Sulphur Lake. Here we found a Ministry of Natural Resources logbook that confirmed that a Ministry crew had passed through the area in the spring. This was positive news as it suggested that all trails henceforth would likely be in good shape.

It was on Sulphur Lake that we decided to pitch camp on a small, but manageable, spit of land on the lake’s western shore. Though not an ideal site, we did manage to stake down our six small tents. The rest of our afternoon was spent swimming and fishing. I was pleased to catch a good-sized pike on a solo canoe outing, as the sky unveiled a broad spectrum of pinks, oranges and yellows with the on-setting dusk.

Day Two – 19.95 Kilometres

I woke up at the cusp of dawn and peeked out of my tent to find clear skies and impeccable conditions. Contented, I sunk back into my sleeping bag and fell asleep again. When I awoke, perhaps two hours later, high winds from the northwest were rattling the spruce trees overhead and a monotone grey sky stretched in all directions.

We set off at 9:30 a.m. and were immediately confronted with a series of four portages in quick succession, including a 200-metre carry to Surprise Lake, a 930-metre carry to Circle Lake, followed by two 90-metre trails to Mississagi Lake. The 930-metre portage was really the only one that provided any challenge, especially as it involved five or six distinct, lung-bursting inclines.

Emerging onto the water from the portage trail on the north end of Mississagi Lake was a welcome reprieve from our slog through the dense forest. The wind pushed us swiftly to the rocky narrows at the end of Mississagi Lake and to the site of the Mississagi Lodge fly-in fishing outpost, where we pulled up on shore and decided to have lunch.

The lodge was situated on a sandy peninsula that separated the Mississagi Lake narrows from Upper Green Lake. This was the former site of a Northwest Company outpost, though no evidence of the old trading station remained. Onshore, we decided to look around to see if anyone was present, but the lodge was entirely boarded up, with docks retracted. We guessed that owners of the outpost decided not to open it for the season as a result of the pandemic.

Upper Green Lake is a large body of water that can become troubling in high winds. Perhaps, the most famous example of this, came during Tom Thomson’s Mississagi trip in 1912, during which a storm swamped his canoe on Upper Green. Thomson and his paddling partner, a man named William Broadhead, were forced to swim to shore as a result of the catastrophe, and narrowly survived.

A fascinating relic of the past, in the form of an old decommissioned fire tower, can also be found on the eastern ridge of Upper Green Lake. With plenty of time left in the day, we decided to paddle over to a marked campsite beneath the tower to see whether a trail up the ridge had endured.

We beached our canoes on the rocky shore beneath the campsite and began climbing the ridge in search of a trail. In the area directly surrounding the campsite we found an incredible amount of rusted out debris, including gasoline cannisters, tools and a St. Lawrence Starch Company container that were clearly several decades old. Beyond this we found the ruins of an old ranger’s cabin, that would have served as the temporary home for any forest service staff who bore the important responsibility of manning the tower.

Our search soon yielded fruit and we found the heavily overgrown remains of the old tower trail. The trail was so overgrown that it would have been impossible to follow had it not been for a scant ribbons of weathered fluorescent trail tape sporadically tied to trees up the ridge.

Having reached the top of the trail, we found the tower itself to be an impressive steel structure that forced its way out of the tangled woods and out above the tree line. A concrete slab at the base of the tower was marked “1957”, presumably the tower’s year of manufacture. For its age, the structure appeared to in good overall condition and fully intact. Lachlan and John both braved the sharp wind and swaying framework, to climb the tower’s ladder to the top – approximately 30 metres. They were treated to a spectacular view of surrounding lakes and countryside. Not wanting to risk a fall, the rest of us climbed to varying heights on the ladder before heading down.

As we returned to our boats, we realized that the wind had intensified on Upper Green Lake. Out on the open water, travelling south, white caps washed alongside our canoes until we crashed against the southern shore. A brief 90-metre hike took us to Kashbogama Lake where a gorgeous sheltered campsite awaited us across the lake.

Despite a chilly wind, our second order of business, after staking camp, was to build a fire and swim in the warm tempestuous summer waters of Kashbogama.

Feeling refreshed, we cooked dinner and turned in for the evening as the high winds continued through the night.

Day 3 – 20.56 Kilometres

After a couple of long days, we decided to slow down our pace a bit and sleep in – we didn’t depart our site at Kashbogama Lake until after 11:00 a.m. Even now, the wind that had pestered us the day before, continued unabated as we pushed toward the Shanguish Lake portage, under featureless grey skies.

From Shanguish onward, the Mississagi increasingly constricts and begins to gradually resemble a river. Although the bulk of our day would be spent paddling twisting sections of flat water, the waterway rarely exceeded 200 metres as it flowed toward Upper Bark Lake.

Just before reaching Upper Bark, we found a nice island campsite on the northwest section of Kettle Lake and decided to stop for lunch. In the distance, to our south, we could see another fly-in fishing outpost.

At the southwest end of Kettle Lake the route once again constricts – this time into two boney rapids. We waded the first of the two without difficulty. After some debate on whether to take a portage trail around the second or line and wade it, we ultimately opted for the latter. The rapid was fairly volumous, but its bouldery character prevented us from mounting any serious attempt at running it. Instead we took our time methodically guiding the boats through the moving water and negotiating tricky footholds on the riverbed. In the end, we emerged unscathed on the other side, leech bites notwithstanding.

On the north end of Upper Bark Lake we found a long, flat island amongst a stand of dying pines that served nicely as our campsite. Upper Bark is a beautiful and serene body of water with a plethora of lonely bays and islands. At the centre of the lake, three small islands, almost identical in appearance, form a peculiar and distinctive triangle. A cloudy sunset soon rolled in, and we built a large fire. The call of the loons skipped over the waters as a light rain began – together these peaceful sounds lulled us to sleep.

Day 4 – 4.84 Kilometres

Although we had enjoyed this little campsite, we decided to make a very leisurely four-kilometre paddle to the island site marked on our map at Bubble Bay. We had reason to believe that this would be a scenic spot and thought it would be nice to change locales without putting in a long day of effort.

The voyage to the island was quick. We passed through an enjoyable little swift as we exited Upper Bark Lake and rounded the corner toward the west to ultimately find our target island sitting off in the distance. The island was a scenic outcrop of tiered rock ledges, capped with a few large windswept pines. There was just enough room for our six tents, though limited firewood would force Devin and I to make a trip to the shore later in the afternoon.

We spent most of the day swimming and fishing, and I also found time to read from a book that I had brought along: Of Time and Place, by Sigurd F. Olson. The opening words of the book are a favourite passage of mine. It is a passage that I thought suited our adventures well, and I knew the lads would enjoy it, so I recited it aloud:

“Over the years the voyageurs, as we called ourselves, made many trips together retracing routes of the old voyageurs in their far-flung travels along the rivers and lakes during the days of the fur trade. No matter where we decided to go it was a joyous adventure, for we were one with them and with the explorers who mapped the far Northwest for the first time.

We ran the same rapids, knew the waves on the same big lakes, and suffered the same privations. Though ours was a modern age, we knew the winds still blew as they had then; the dim horizons looming out of the distance were no different from the mirages they had known. In the mornings we saw the same mists, resembling white horses galloping out of the bays. We knew all this, but most important was the deep companionship we found together. We had been most everywhere, and for us the North was much more than just terrain. We were part of its history.

Like men who had been in combat, we looked at the world through different eyes, for we had been tested in the crucible of the wilderness and had not failed. The values we shared from our common experience are hard to explain, but without them life has no purpose. In my homeland of the Quetico-Superior and the wilderness canoe country, I often think of these values, which are in the land itself and in its rich history. The real importance of this region I know so well is not the vast deposits of minerals or timber or the part they play in our economy; the real importance lies in the values we find there and that we take with us when we leave, although we may not quite understand them.” (Olson, 1982)

I remained in my canoe by myself, for most of the final hours before sundown, casting a line for walleye and bass. Devin and Kevin both had success fishing off the rocks and John paddled out to explore the lake on his own, while Lachlan and Jono cooked fresh bread over the fire.

It was the golden hour now. The sun crept out from behind the curtain of dark clouds on the western horizon and bathed our jagged island campsite in a brilliant orange light. The island, with its iconic windswept pines, about 20 metres before me, was thus transformed into a monolithic silhouette etched against a radiant backdrop. Turning and gazing out over the expanse of dark waters to my east, gentle waves lapping against my canoe, I could see that the treeline on the far shore was now set ablaze with a glow so pure that it seemed to fall from heaven itself. The scene was one that travellers of this remote landscape, through the ages of old, would have known well. This was a scene that would have doubtlessly stirred – as it had for us – their admiration for all the natural world and instilled in them a profound zeal for life.

As the evening set in, we gathered around the campfire and savoured the expertly prepared bread baked by our companions. The clouds had begun to dissipate, stars emerged and a spectacular full moon rose between them to the east. From somewhere off in that same direction, the loons called out again.

Day 5 – 24.17km Kilometres

We awoke to harsh winds from the west and we could tell from the swirling clouds that rain threatened. Thus, the primary drawback of our island site – exposure to the elements – was quickly laid bare.

Our group had spoken briefly the day before about the two route options heading out of Bubble Bay and we now needed to make a decision. The first option followed the main course of the Mississagi via the southeast extent of Upper Bark Lake and through a scenic collection of cliffs and islands before reaching an old Forest Department cabin that once temporarily housed Grey Owl. The distance between our island and the cabin via this route was approximately 13 kilometres.

The second option was to take a shortcut through a marsh, known as Presage Bay, at the south end of Bubble Bay. This route risked a mucky slog through marshland and would require travel over two unmaintained portages (500 metres and 100 metres respectively) of unknown quality, but would get us to the cabin in little over three kilometres.

With a strong possibility of rain, and an apparent lack of campsites ahead, we opted to take the latter of the two options and press on as far as possible. This turned out to be the right call given our scenario. Not only was the marsh at a good water level, but the portage trails leading to the cabin were in decent enough condition too, aside from a few blow downs.

Grey Owl’s cabin is found at the end of the 100-metre trail that links the Presage Bay shortcut back to the Mississagi River. In the early 1900s, this cabin served as the headquarters of the Mississagi Provincial Forest Reserve. It was in these early days that Grey Owl stayed here while on duty as a forest ranger, and even carved his initials “AB” on the cabin’s interior in 1914. Today the cabin abuts a well-maintained private fishing lodge.

As our group approached the end of the 100-metre trail, we were excited to spot the cabin on the left. The building had clearly seen finer days. Its walls, except at their rotting base, were constructed of large, hefty log beams, perhaps of cedar; the gable roof was weatherproofed with faded red shingles and though the solitary window was boarded up, the door was jammed open. Peeking our heads in, we could clearly see that wild animals had been dwelling inside from an arrangement of torn and chewed articles on the floor. The cabin contained a variety of thoroughly aged items – pots, pans, tools, bedding – strewn about in disarray. Still, it was very easy to imagine how this rustic dwelling must have looked at its peak.

It was certainly enthralling to think of all the travellers who had passed through here over the years and the stories they must have held of their own adventures in this land. The walls on the cabin’s interior were covered in hundreds of carvings typically denoting the passage of former travellers. While the location of Grey Owl’s name was not readily apparent on the walls, we could spot carvings as old as the early 1930s and thought about how the world would have been back then.

As we left the cabin and continued on our journey, I couldn’t help but feel a bit of sadness for the state of this fascinating place. Though run down, it was by no means beyond repair as its bones were still strong and hearty. With some care, fires could again someday warm the walls of this century-old relic.

We were now entering the Mississagi River proper. From this point, for the next 30 kilometres or so, the Mississagi cuts a path through the land in the shape of a large “W” and is characterized by innumerable rapids and falls, interspersed by flat water. At the end of this colossal zig-zag the river flushes into a vast and spectacular wetland known as “Majestic Marsh” or “The Maze”, en route to the big waters of Rocky Island Lake.

The first three-kilometre section of river following Grey Owl’s cabin sits directly into the prevailing wind. Although a bald eagle floated effortlessly above us, we were faced with a punishing headwind. As we thrashed our way down the river, to the northwest, the dark swirling clouds above finally gave way to a thick, cold, torrential rain. Patches of blue sky ahead, however, gave us hope and the rain subsided as the river narrowed and swung to the southwest.

Over the next few kilometres we easily navigated a number of swifts, before stopping for lunch at the cobbly base of a boney class I rapids. Not far after this set, the river again swung to the northwest and we were forced to paddle into the unrelenting headwind for another four or five kilometres. As we forged through the wind, here, I noticed several campsites in this area that were not marked on my map.

Our next major obstacle was a rapids marked with a 150-metre portage trail on river left. In scouting the top of the rapids, we could see that the river tightened into a large chute followed by a series of rocky drops. Recognizing that we could not run this part of the river, we hauled our gear over the trail. At the end of the portage, we found that the trail opened into a large, flat-rock clearing with plenty of room for tents. Alongside the clearing, the rapids came to a turbulent culmination of white spray and froth as the river cascaded over various rocks into a large black pool.

Realizing it was getting late in the afternoon, we debated pushing forward to sites at Split Rock Rapids or Hellgate Falls, two kilometres and five kilometres further downstream, respectively. Ultimately, it was apparent that we had stumbled onto a rare and beautiful campsite that afforded us wide open skies (perfect for stargazing), good fishing potential and gurgling white-water in the background. We decided to unpack here and quickly pitched our tents before taking a much-needed dip in the rapids.

In the evening, with wispy indigo skies above and dozens of swallows fluttering through the warm, fresh summer air, we fished in the dark eddies at the bottom of the cascade. Devin was the first to land a good-sized fish – a walleye – that we dispatched, filleted and took up to our campfire. Jono had brought lard and fish batter along and rapidly set to the ritual of preparing a fine meal, as a broad blanket of stars became clearer overhead.

Day 6 – 18.43 Kilometres

Our goal for the day was to make the 25-kilometre paddle from our current location to the mouth of the Abinette River. Considering the terrain, and especially the numerous rapids and obstructions that lay ahead, we knew that this would be a tricky feat.

We departed our site around 10:30 a.m. and followed the winding river through the dense, mixed boreal forest that surrounded us. Our first rapids of the day were a short class I, that we tackled without difficulty. Immediately thereafter, a more technical set presented itself. In scouting this second rapids from the 60-metre trail, we noted that the route through would involve dodging a strainer, before cutting diagonally across the flow and exiting via a frothing chute at the bottom. Lachlan and I were the first to run the set and managed to get to the bottom without incident. The other two boats managed their way through the rapids as well and we all celebrated at the bottom with shouts of triumph.

Further downstream we successfully navigated a charming set at Splitrock Rapids and finally came to the top of Hellgate Falls. As the name implies, Helllgate involves a mandatory portage (of about 680 metres). Here, the river narrows aggressively and falls over 30 feet in a series of violent drops. After moving our gear over the portage trail, and resolving to eat lunch here, we returned to the top of the falls and bushwhacked along the rugged shoreline to catch spectacular views of the maelstrom.

Beyond Hellgate, we encountered a long, technical, rocky class II+ rapids with a 180-metre trail bypassing it on river right. A lengthy discussion between Lachlan and I on the runnability of the set concluded with a mutual decision to bypass the section altogether. While I had argued to take the rapids on, walking was probably the best call in the end, in order to avoid damaging the boats on the submerged boulders throughout the set.

The following two rapids, avoidable via 100-metre and 450-metre portages, respectively, were easily navigated, though the latter was quite rocky.

Our party now faced an important decision. It was about 4:30 p.m. and we had arrived at a well-used campsite, accessible by 4×4 via a logging road to the south. In front of us lay the entire expanse of the Majestic Marsh and the next site appeared to be approximately seven kilometres downriver. Admitting it would probably be foolhardy to push on through the meandering oxbows of the marsh, which undoubtedly held no viable places to construct a bush site, we decided to settle for our present location.

Though the site was clearly well-used, as the trash in the firepit and fresh all-terrain vehicle tracks suggested, at least the it held ample flat space, plenty of firewood, and good protection from the elements. Surrounding the site were a series of apparently well-trodden trails that shot off into the bush in various directions. Having explored the trail to the north of the site, I concluded that the area must be used as a base for trapping or hunting.

Following a nice meal by the fire, we withdrew to the shore where a fabulous, clear arrangement of stars shone brightly and reflected off of the shallow rippling waters of the river. We searched the sky to the northwest where we knew that the NEOWISE comet could potentially be seen. Instead of spotting the comet, though, over a period of several minutes, seven or eight meteors flashed over the silhouettes of the pines across the river. Some of these burned silently across the sky with incredible brilliance.

Day 7 – 28.30 Kilometres

Our late 11 a.m. departure this morning was perhaps an indication that we were tired from several long days of paddling and portaging. We were happy to see, however, that the river was moving along at a good speed downstream of our campsite.

The river was generally quite shallow now, with sand, rocks and long underwater grasses visible below our boats in most places. Within a couple of kilometres of the site, the rocky, elevated topography that had previously surrounded us, began to open up. It was not that the river became wider, per se, but that the terrain became more expansive and open with large ridges bulging from the earth in the distance. Suddenly, we found ourselves surrounded by cattails and other vegetation characteristic of wetlands.

The entrance to the Majestic Marsh is thus, quite clear. What was less certain for us was the navigability of the wetlands, which are said to change dramatically depending on water level. In fact, we had read a story, from 2013, of a couple that had become disoriented and lost in marshes here for two days, and were lucky to have been saved by a passing canoe group. While we weren’t worried about getting lost in the marsh, we were somewhat concerned about a tedious slog through a frustrating web of channels and dead ends.It turns out those trepidations were entirely unfounded. Majestic Marsh was an incredibly beautiful landscape and an absolute joy to paddle. Within the marsh, the river snaked peacefully through a clear path of golden reeds, and was teeming with wildlife. Mergansers and golden eyes, grey jays and other birds cruised the waters and skies alike; a large beaver swam directly under our canoe.

Our time in the marsh passed too soon, and once again the landscape surrounding the river closed in. We stopped for lunch atop a rough, riverbank campsite near the Mississagi’s confluence with the Abinette River and ran a small ledge rapid a kilometre or two later (which happened to swamp Kevin and Devin’s boat).

A few more kilometres on, we bypassed Bulger’s Folly, a fork in the river that takes paddlers on an unnecessary three-kilometre detour. In order to avoid the detour, it is essential to stick to the righthand channel at the fork. At this interval, the river starts to show signs that it is gradually opening up into a massive lake. A riverside cliff we encountered, for instance, showed a high waterline that was eight feet above our current levels. We knew, of course, that this could be explained by the fact that Rocky Island Lake, which now lay only five or six kilometres to the west, was a dam-controlled reservoir for the hydro-electric generating station at Aubrey Falls and held a large surplus of water every spring.

At this point we began searching for sites, but having found few that suited our needs we decided to pull out at a beach, crowned by a bone-dry mudflat, about two kilometres east of Third Island near the end of the river. An investigation of the area suggested that the mudflat was commonly used by moose (large prints could be found in various places here), but the spot provided an excellent vista and sufficient flat ground for our tents.

A campfire on the beach was now in order, which we supplemented with swimming. At sundown Lachlan and I paddled out onto the water to try to bag a fish, but had no luck. We were treated, however, to a fine tangerine sunset to the west as consolation.

There were now only 35 kilometres remaining on our voyage down the Mississagi.

Day 8 – 19.60 Kilometres

When morning came, it appeared that our premonitions about wildlife in the area were warranted. John told us that he had been stirred in the early morning hours by a moose or another large animal crashing around in the forest behind the mudflat. I had similarly awoken, around 2 a.m. to the sound of a beaver slapping its tail on the water along to the river.

Today was a significant day for our trip as we had now reached Rocky Island Lake and were drawing ever closer to the end. We knew this lake presented a special challenge. The prevailing winds had cut consistently from the west for the entire trip and we were entering Rocky Island from the northeast corner with a southwest destination. Our path would take us over two massive open water crossings, likely into strong winds and waves.

As we made our way through the final portions of the river and around the corner of Sprat Bay, our fears were confirmed. The winds were strong and had whipped up tumultuous white caps as far as the eye could see across the eastern branch of this massive lake. It would be extremely reckless to attempt a crossing in these conditions and so we knew we’d have to pick our way south along the east shore, completing a series of smaller crossings instead.

Despite the fact that it is a reservoir, Rocky Island Lake is an incredibly unique, beautiful and still wild place. As its name suggests, the lake is speckled with a seemingly endless array of rocky islands, rocky shorelines, bays and cliffs that could easily accommodate a week or more of exploration by canoe. Adding to this, low water lines, characteristic of the reservoir at this time of year, mean that the exposed beaches and outcrops of the lake have virtually limitless opportunities for camping.

It is notable, for trip planning purposes, that Rocky Island Lake and its drainage waters at Aubrey Lake, together hold three access points, including Rouelle Landing, Rocky Island Lake Road and Aubrey Falls. It was the furthest of these, Aubrey Falls, that was our goal.

Having passed Sprat Bay and Policy Bay we picked our way to Imagine Point, Darlene’s Point and Jess Island before crossing north and landing at an outcrop for lunch at the entrance of Stimpy Channel. Here we prepared food and had a small fire, as we discussed our objective for the rest of the day. With the constant winds, the sun had now faded in favour of dark clouds and rain seemed certain. We set our sights on an island campsite located about 10 kilometres to the west at the opening of Seismic Narrows and began paddling through the tall cliffs of Stimpy Channel.

Headwinds continued from the west, but as we entered the main body of Rocky Island Lake, where the longest crossing awaited, we were fortunate to find the severity of the wind had waned. There were still white caps ahead, but their sting had been all but muted. This being the case, we set out on the large crossing to the south end of Dayton Island.

Near the tail end of this island, Jono remarked that he saw something swimming in the water ahead of us. On approach, he shouted that it was a bear that appeared to be making its way to the rocky beach at the southern point of the island. Each of the three canoes took care to give the animal a wide berth so as not to frighten it while it swam to shore. Upon landing on the island, the medium-sized black bear charged up the shore, taking one glance back at us, and was gone into the dense bush in a flash.

As we continued our crossing to Yoohoo Island, rain began to fall steadily. It was here that we passed the first people – two motorboats heading east on the lake – that we had seen since the day we embarked on our journey. One of the boats, apparently surprised to see us, slowed down and its driver asked whether we were lost.

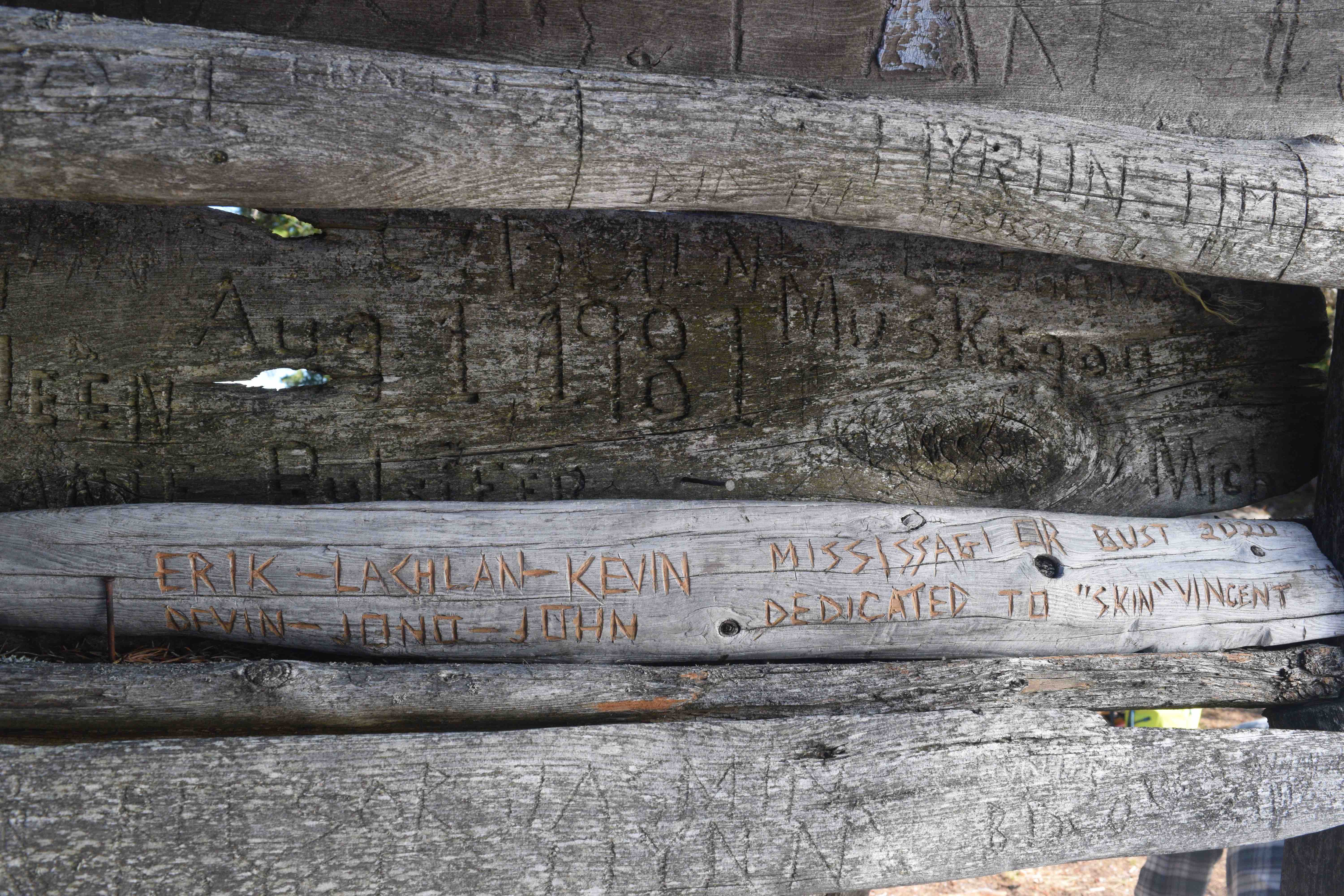

Soon, with an intensified rain pelting down on us, we landed at the island site near Seismic Narrows. The island was a teardrop shaped outcrop of rock, with plenty of space for tents, and crowned with dozens of jack pine. Its most peculiar feature, however, was what appeared to be an old, dilapidated driftwood fort, approximately four metres long, four wide and two high, that was constructed near the fire pit. The fort listed heavily to one side as some of its support beams had rotted out over the years. While the interior included various tables and benches, also constructed of driftwood, most of them were heavily decayed and unusable. Upon further examination of the innumerable carvings attached to the structure, we found that the fort named, “Driftwood Lodge”, was constructed by two fellows, named Jack Brautigam and Don Rosinski in 1981.

Given the unrelenting rain, we did not linger at the fort for long, and each swiftly moved to set up our tents.

There was still plenty of daylight left, and in order to make our camping experience more communal, Jono, Devin and Lachlan hoisted a tarp onto the roof of the Driftwood Lodge and built a small campfire inside. The Lodge turned out to be a perfect refuge from the rain, and we passed most of the remaining hours of the day warm and dry under this little shelter.

We calculated that we were now only 18 kilometres from Aubrey Falls and the end of our trip. In view of savouring the journey a little bit longer, we decided to take a rest day at this beautiful island, hopeful that the weather would improve.

Day 9 – 0.00 Kilometres

Emerging from my tent late in the morning, I was welcomed by a warm, cloudless summer day. With an open agenda, we cooked up our breakfast late in the morning, while thinking of things to fill the time.

We started the day’s activities with a refreshing swim. The main communal portion of the campsite, by the firepit, was bounded by a rock ledge that hung approximately six feet out of the water. This, of course, served as a perfect platform to jump into the cool dark waters off the island’s south side.

The next order of business was to right the listing driftwood shanty and buttress its aged frame with a few spare beams salvaged from the shore. Generally, I disapprove of any measures taken within wild areas, while on our trips, that alter the physical environment. It is of paramount importance, in my view, to leave all backcountry areas, in the state in which they were discovered, as far as possible. I believe that we must, at all times, engage in healthy reciprocity with the forest. In this, we have a responsibility to act keenly as stewards of the flora, fauna, and physical environment, but at the same time, take only the essential things we need. I would have never undertaken to build this type of shelter, myself, unless perhaps in some dire survival situation. However, this building had been now been in this spot for almost forty years – it was older than me. The structure was unobtrusive and offered shelter, protection and fine memories to many dozens of travellers over the years. The shelter was now as much a part of that campsite as the jack pines that clung to its rocky crown. Thus, I did not object when one of the lads suggested that we push the tilting frame upright and reinforce it.

In the mid-afternoon, Lachlan, Devin and I paddled across the channel to our northwest and bushwhacked to the top of a 30-metre cliff overlooking a broad stretch of this portion of the lake. The hike up was relatively easy and the view afforded a panorama of the lake’s sparkling waters and lonely islands encircled by lush rolling hills of deep green. We stayed here and admired the fantastic view for quite a while before making our way back to camp.

As dusk fell, Jono and Lachlan cooked another round of fresh bread over the campfire. I occupied myself by picking up a flat piece of driftwood from the floor of the shanty and carving into it:

“ERIK – LACHLAN – KEVIN – DEVIN – JONO – JOHN

MISSISSAGI OR BUST 2020

DEDICATED TO ‘SKIN’ VINCENT”

Once completed we mounted this plaque onto the wall of the Driftwood Lodge amongst countless others. With this we felt our contribution to the lodge was complete.

For the sake of context, it is worth mentioning that none of us really knew who, or what, “‘Skin’ Vincent”, was. “‘Skin’ Vincent” was merely a name that we had spotted, several days prior, scrawled on the wall of Grey Owl’s cabin. We thought the name to be comical, and in a way, I suppose we had adopted ‘Skin’ as our seventh paddling companion. Ultimately, we agreed that it was fitting to dedicate our adventure to this apparition.

With night upon us, a strange, eerie blood moon began to emerge over the horizon amongst the clouds. The winds now picked up and whistled through the pines. I felt sad to be leaving this wild land.

Day 10 – 15.4 Kilometres

Today would be the last full day of the trip. We targeted one final campsite approximately 15 kilometres away on Aubrey Lake at a place called Carter Island.

The weather today was fair and sunny with a slight coolness hanging in the air. A west wind greeted us as we paddled through Seismic Narrows and amongst its sheer stately cliffs. Here we came upon a pair of canoeists heading out from Rocky Island Lake Road on an overnighter.

We soon found ourselves turning the last corner of this massive lake and pulling our boats out to the left of the Rocky Island Lake Dam – a large storage dam, built in 1949, that preserves water above the Aubrey Falls hydro-electric generating station.

The trail around Rocky Island Lake Dam is 720 metres in length and follows a well-used service road. The end of the portage trail is indistinct and generally involves finding a way down to the river through one of the numerous paths off the main roadway.

Upon completing the portage, our group hiked upstream along the river to take in views at the base of the dam and have lunch. It was very difficult to imagine how this portion of the Mississagi must have looked before the construction of the dam.

A kilometre of paddling downstream from the dam took us into Aubrey Lake. Much like Rocky Island Lake, Aubrey Lake is rugged and picturesque with massive hills and towering land formations rising regally from its shorelines. We landed at our planned site on the east side of Carter Island, and found that it would be a tight squeeze. We considered other options and even checked a marked site on the opposite side of the island, which was even smaller and more overgrown, before agreeing to make the initial site work. John and I both were forced to head back in the bush, away from the shore, to hack out our tent spots.

Ultimately, we were quite happy with this campsite. Though it held limited flat ground, it provided a rocky peninsula with a dark bay off the north shore which would serve well for fishing. The site also afforded a terrific view of Aubrey Lake with a seemingly endless northeast vantage of sprawling island studded waters bounded by a large range.

Within two hours of landing at Carter Island, however, the weather took a turn for the worse. Dark, brooding clouds formed to the west and high winds picked up – we could see rain rapidly approaching over the lake. Before it reached us, a tarp that we had positioned over our common area rattled violently in the wind and was torn. Kevin and Jono’s tents, which were anchored to the ground with stones, flipped suddenly in howling wind and we scrambled to re-anchor them as large heavy drops of rain pummelled the campsite.

As I ran back into the bush toward my tent to find relief from the storm, John met me on the trail and, struggling to make his voice heard over the chaos surrounding us, pointed out a dead, medium-sized spruce tree that was breaking at its base in the wind. Before our eyes and to our astonishment, the tree fell slowly through the forest before coming to a resting place on the forest floor – right in between our tents which were spaced approximately six metres apart.

With all men in their respective tents, thunder and lightning began to crash overhead. At its peak, thunder boomed about one or two seconds off of a flash of lightning, indicating that the lightning had struck no more than approximately 600 metres from our campsite. As the electrical storm passed over, I took the precaution of crouching atop my sleeping pad to insulate myself from the ground, while trying my best to read my book.

Within the next hour, the rain had ceased entirely and I emerged from my tent to find tamer skies of light grey and unbelievably calm lake waters surrounding our island. Lachlan pointed to the east at the dwindling remnants of a rainbow.

We saw the existing conditions as a perfect excuse to fish. Amongst the group, we bagged several bass and walleye as the light grey skies developed a strong pink and purple hue. Jono and John set to work preparing our haul over the stove and campfire, and we capped our final night in the woods with a delicious feast.

Day 11 – 3.8 Kilometres

Having resolved to wake up early and paddle the remaining four kilometres to our cars at the Aubrey Falls spillway, we found ourselves on the water shortly after 7 a.m. The cloudless skies were a wonderful colour of deep blue and the horizons of this ancient land, with its mammoth cliffs and ridges, were fully shrouded by thick clouds of morning mist. It was if we were paddling through the clouds of heaven.

On we paddled, to the north and into Brookfield Bay, passing a flock of ducks cruising along the rugged shoreline. We could now see the bright red warning booms of the Aubrey Falls hydro-electric generating station before us and hugged the righthand side of the river to our takeout point at the spillway.

Finally at our journey’s end, we pulled our boats on shore, shook hands and celebrated with some warm beers that we had left behind in our cars.

To cap off our adventure, once our vehicles were loaded, we drove around to the main entrance of Aubrey Falls Provincial Park and hiked the short trail to view the falls itself.

Aubrey Falls is a spectacular cataract that drops 53 metres over ten distinct segments containing upwards of 25 chutes that cut through orange granite. Despite the fact that the falls are dam controlled, all paddlers of the Mississagi should stop here to enjoy its incredible majesty. The best view of the falls comes at the end of the trail, past the Tom Thomson memorial, past the footbridge that spans a chasm over the river and up to the top of the adjacent ridge.

Epilogue

Our full journey on the Upper Misssissagi spanned 11 days, 10 nights, 172.4 kilometres of travel, including 19 portages. Altogether we paddled and hiked for over 36 hours, held an average moving pace of 4.7 km/h and dropped 64 metres of elevation between Mississagi Lake and the top of Aubrey Falls.

Although the river has been indelibly impacted by the hand of industry – logging and energy projects are clear examples – the upper stretch of the river to Aubrey Falls shows little evidence of this. For many, it may be disheartening to think of the influence that humans have had in altering this waterway, especially south of falls, but this river is still one of the finest I’ve had the joy of paddling.

The Mississagi is a river that deserves to be travelled over 10 days or more. Its incredible and varied scenery, biodiversity, and unique history command sufficient time to explore and savour this wild place. This is, after all, the river of a hundred ghosts – a place of grand adventure, through which many passed and where few tread. And yet signs still endure: the fire tower; the old cabin; the lodge made of driftwood; the centuries-old portage trails themselves. This river has seen generations of Indigenous hunters and trappers; it has seen the great canoe brigades; the lumberjacks; a great artist; and a conservationist and a writer, who once scribed the following words:

“There comes the song of a white-throat, high in the trees, above me. I hear the roaring of the River, the endless noisy march-past of the River; and the distant rumour of the rapids sounds like the conversation of the Dead.

The plaintive, unfinished melody of the little bird trailing off into utter silence, burdened with all the sadness, all the heart-throb, all the glory of the North, and infinitely beautiful, sounds the Requiem of the Lost Brigade–singing, singing in a far-away cadence, farther and farther–fainter –fainter–” (Grey Owl, 1936).

Wonderful photos!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Erik: Wonderful story, great writing and photo’s. I traversed much of this route as a L&F employee in 70’s and 80’s. My wife and I actually stayed 2 night in Old Chief Ranger cabin in 70’s when in good shape. I have photo of Archie Belaney’s name written on interior “A.Belaney, Bisco, ’14.” I am a graduate of Ontario Forest Ranger School, 1967 and our alumni Ass’n are trying to encourage Ontario Parks, current owners to save the old cabin, either restored in-situ or dismantled and restored somewhere else ie. Bushplane Museum in Soo . I wrote piece in Ontario Historical Society , issue 209, December 2018 about Cabin. Would love to hear from you.

LikeLike

Hi Will, my apologies for the tardy response – its been a while since I logged into the site (finally decided to write and post a new article). I just pulled up and read the interesting piece you wrote about the cabin (which I found here: https://ontariohistoricalsociety.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/December-2018-OHS-Bulletin-209-FINAL.pdf) and wish I had seen this earlier! Really fascinating details on the history of this place. We had wondered about where and in what form Belaney’s name was scrawled. The cabin is quite the structure, but definitely has seen better days – as you well know. The fact that the roof is still in such excellent condition is probably the only reason it might still be salvageable.

LikeLike